The Romans practiced crucifixion – literally, “fixed to a cross” – for nearly a thousand years. It was a public, painful, and sluggish form of execution, and used as a method to discourage future crimes and embarrass the dying person. Considering that it was done to thousands of individuals and involved nails, you’d most likely presume we have skeletal evidence of crucifixion. However there’s only one, single bony archeological evidence of Roman crucifixion!

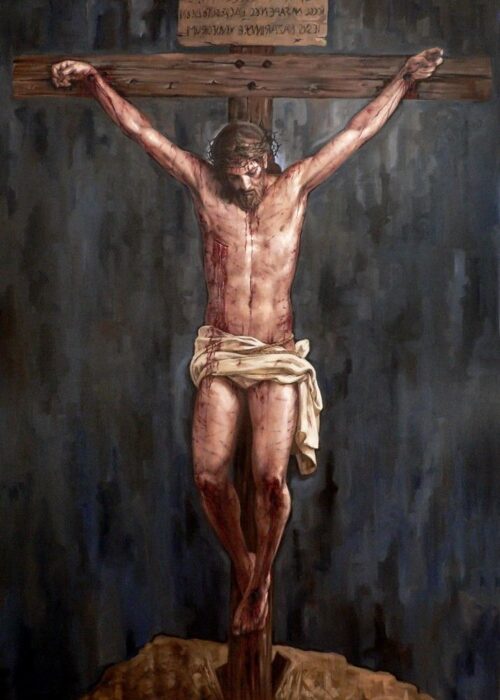

Crucifixion appears to have actually originated in Persia, however the Romans developed the practice as we know of it today, utilizing either a crux immissa (similar to the Christian cross) or a crux commissa (a T-shaped cross) comprised of an upright post and a crossbar. Generally, the upright post was erected first, and the victim was connected or nailed to the crossbar and after that raised up. There was generally an inscription nailed above the victim, noting his specific criminal offense, and in some cases victims got a wooden support to sit or stand on.

The only previously discovered archaeological evidence comes from a 1968 Jerusalem excavation performed by Vassilios Tzaferis of tombs from a huge Second Temple Jewish cemetery (2nd century BCE to 70 CE) in the Giv’ at HaMivtar area. Inside a typical rock-hewn tomb of the era, Tzaferis found, among other items, a number of bone receptacles. Inside one ossuary lay the bones from 2 generations of males, one 20-24 year old, and the other a mere 3 or 4 year old.

On the heel bone of the older male was discerned an 18 cm (7-inch) nail, upon which was discovered some 1-2 cm of olive wood– remnants of the cross from which he was hung, researchers concluded. Upon publication, the world heralded this unique evidence of the historicity of crucifixion.

When nails were involved, they were long and square (about 15cm long and 1cm thick) and were driven into the victim’s wrists or lower arms to fix him to the crossbar. Once the crossbar remained in place, the feet might be nailed to either side of the upright or crossed. In the first case, nails would have been driven through the heel bones, and in the 2nd case, one nail would have been hammered through the metatarsals in the middle of the foot. To hasten death, the victim often had his legs broken (crurifragium); the resulting compound fracture of the shin bones might have resulted in hemorrhage and fat embolisms, not to mention substantial pain, triggering earlier death.

Like death by guillotine in early contemporary times, crucifixion was a public act, but unlike the speedy action of the guillotine, crucifixion involved a long and painful – literally, excruciating – death. The Roman orator Cicero documented that “of all punishments, it is the most cruel and most terrifying,” and Jewish historian Josephus called it “the most wretched of deaths.”

So crucifixion was both a deterrent of further crimes and a humiliation of the dying person, who had to spend the last days of his life naked, in full view of any passersby, up until he passed away of dehydration, asphyxiation, infection, or other causes.

Since the Romans crucified individuals from at least the 3rd century BC up until the emperor Constantine banned the practice in 337 AD out of respect for Jesus and the cross’ powerful symbolism for Christianity, it would follow that archaeological evidence of crucifixion would have been discovered all over the Empire.

And yet only one bioarchaeological example of crucifixion has actually ever been discovered.